I’m not Lonely Planet’s biggest fan.

Why? You ask.

Because in many ways they uphold the very same ideas that they supposedly seek to get rid of.

Mark Twain (n.d.) famously wrote: “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts,” and Lonely Planet (LP) too believes travel can be a force for good, reducing cultural differences and inequalities.

Whilst I don’t necessarily disagree, my problem is that the notion that travel is the best way of getting rid of narrow-mindedness, is based upon the assumption that ‘foreign’ cultures are unknowable in the first place, and it is only by spending time with these Others that the traveller can accept their shared (albeit, diverse) humanity, rather than it being a given despite their perceived differences.

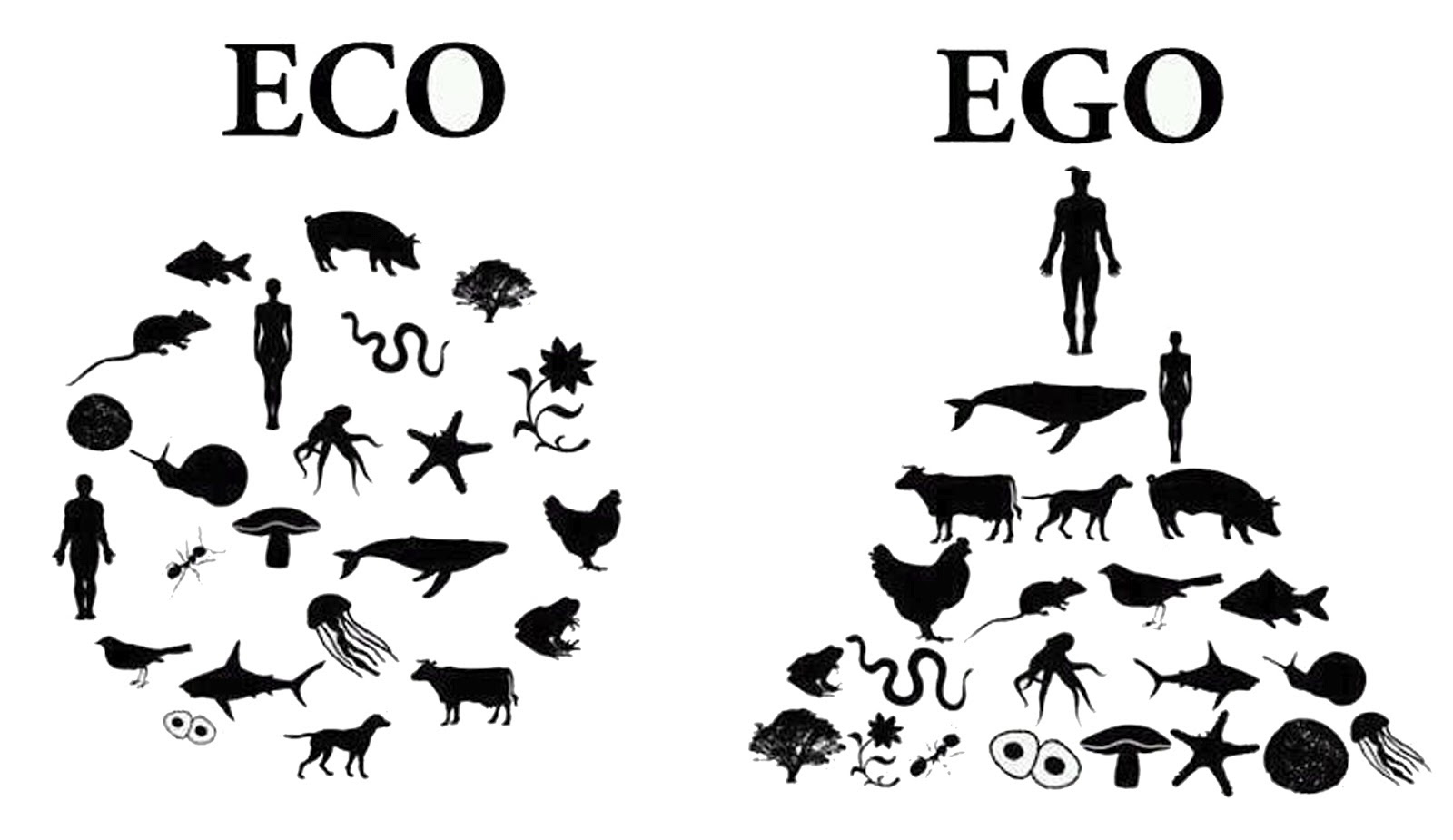

This process of inspiring change within the traveller is often founded on a binary between the self and an exotic Other, where the self travels to “’exotic’ third world destinations” that bear absolutely no similarity to the world the traveller has come from. LP features predominantly Western writers providing information for other Western travellers about ‘exotic’ (read: non-Western/alien) destinations with language that heavily emphasises the traditions and “Otherness” of the people they write about. By privileging the Western Orientalist voice over the local, it becomes a vaguely colonialist form of communication that only further marginalises people outside of the “Western world” – they are unable to create themselves, rather, they are whatever the writer shapes them into being.

This is not just me as an anthropology student blowing things out of proportion; Soranat Tailanga’s (2014) research into the influence of English travel writings on the tourist’s conceptualisation of Thailand found that this medium is particularly powerful in influencing the tourist’s perception over a country and culture. Take the way LP writes about Myanmar (Burma), for example. A country in the exotic South East Asia, it is described as a place where “the traditional ways of Asia endure” (LP 2019), and exploring it can “often feel like you’ve stumbled into a living edition of the National Geographic, c 1910! For all the momentous recent changes, Myanmar remains at heart a rural nation of traditional values” (LP 2019). This language is quite problematic; particularly since you don’t find LP writing about the “traditional ways” of England, America or Australia. These Western places are not exotified, rather it is the charm of their cities and landscapes that provide the traveller with fulfilment rather than the people. An implication emerges, then, that exotic cultures, with their strange traditions and ways of life exist, are frozen in time, for tourist consumption and benefit.

This idea of culture as static is only exacerbated when a city has the audacity to industrialise and the familiarity of it loses a city’s exotic, alien appeal. According to LP, Mandalay, Myanmar’s second largest city “will never win any beauty contests” (LP 2019) due to the “haphazard construction boom that was never about aesthetics. An ever-growing number of motorbikes and cars clog the roads, too, making for a sometimes smoggy city” (LP 2019); “beyond a functional grid, it doesn’t have a ton of immediate appeal” (LP 2017). Maybe this is just my subjective opinion, but I don’t think “foreign” cities exist to appeal to a tourist’s aesthetics, just as people in these places don’t live to aid the tourist in their process of self-discovery. Culture is not guarded by an Other, neither is it so inherently incomprehensible to the Western traveller that it is something that has to be experienced to be believed. Rather, the “culture” one seeks is more likely people just trying to live their own ordinary, startlingly familiar lives. Essentially, tourism elevates these cultures into something exotic and magical, where the people of this culture merely just see it as their boring, everyday life.

There are a lot of similarities that can be drawn between travel and ethnographic writing. Like anthropology, travelling involves “the human capacity to imagine or to enter into the imaginings of others” (Salazar, 2014 p. 1) for a particular audience, often to better understand and overcome inequalities in this world. However that also means that they are often complicit in upholding structures that silence and strip agency from the very same people they write about. The ethics of travel and representation are becoming increasingly complicated, both as a tourist and as an anthropologist, but it doesn’t take much to explore this world with a slightly more critical eye.

Banner Source: LP

(All other images are my own)

References:

Abbie’s Emic vs Etic article

Harrison, J 2006, ‘A Personalized Journey: Tourism and Individuality’, in V. Amit and N. Dyck (eds.), The Cultural Politics of Distinction, Pluto Press, London, pp. 110-130.

Imogen’s articles on Anthropology’s past and Ethnocentrism

Lonely Planet 2017, Introducing Mandalay, viewed 1 June 2017, <http://www.lonelyplanet.com/myanmar-burma/mandalay/introduction>

Lonely Planet 2019, Introducing Mandalay, viewed 7 June 2019, <http://www.lonelyplanet.com/myanmar-burma/mandalay/introduction>

Richmond, S 2019, Introducing Myanmar (Burma), viewed 7 June 2019, <http://www.lonelyplanet.com/myanmar-burma/introduction>

Lonely Planet 2017, Introducing Singapore, viewed 1 June 2017, <http://www.lonelyplanet.com/singapore>

Salazar, N.B., and Graburn, N.H.H., 2014, Tourism Imaginaries: Anthropological Approaches, Berghahn Books, New York.

Talianga, S 2014, ‘Thailand through travel writings in English: An evaluation and representation’, Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, vol. 37, pp. 1-6.

Twain, M n.d. (orig. publ. 1869), The Innocents Abroad, Harper & Row, New York.

See Also:

Lani’s article on Eat, Pray, Love

Johnson, A.A. 2007, ‘Authenticity, Tourism, and Self-discovery in Thailand: Self-creation and the Discerning Gaze of Trekkers and Old Hands’, Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 153-178

Kraft, S.E. 2007, ‘Religion and Spirituality in Lonely Planet’s India’, Religion, vol. 37, no.3, pp. 230-242.

Kravanja, B 2012, ‘On Conceptions of Paradise and the Tourist Spaces of Southern Sri Lanka’, Asian Ethnology, vol. 71, no. 2, pp. 179-205

Lisle, D 2008, ‘Humanitarian Travels: Ethical Communication in “Lonely Planet” Guidebooks’, Review of International Studies, vol. 34, pp. 155-172